Dear wine lovers, let’s discuss sherry. Have you heard about it before? What comes to your mind when you think about it? Rather sweet, technically a wine, but more like a liqueur? At least in Poland, from the perspective of an average wine drinker sherry remains quite an obscure drink. In most local wine stores and mainstream supermarkets, usually the only sherry on offer is an odd bottle of Pedro Ximenez. This creates a rather misleading picture of sherry wine. The distinctive and diverse sherry microcosm is lost. Not many wine regions can boast such unique wine making traditions and truly diverse types of wine; unlike any other in the wine world.

Sherry is made in southern Andalusia, Spain. Three towns north of Cadiz are known to create the so-called “sherry triangle”. I was very lucky this autumn to spend a few weeks in the region and managed to visit two of these sherry towns: Jerez de la Frontera (Jerez = sherry, in Spanish) and El Puerto de Santa Maria. They are not the typical pueblos blancos associated with the Andalusian countryside. They are rather big, urban areas with small historic city centres. What was unique were the large bodegas (wineries where sherry is made) which are immediately visible to any visitor entering the town. Even today, the bodegas are situated in prime city locations taking up sizable portions of the total square footage of the sherry triangle cities.

I visited two bodegas – Lustau in Jerez and Gutierrez-Colosía in El Puerto de Santa Maria. The former is a big, corporate operation while the latter, although of a decent size, is still a family business. In both places I opted for an extended guided tour and tasting. This way, I could fully admire the incredible interiors of the bodegas, often likened to cathedral churches thanks to their lofty architecture. This also allowed me to finally learn what sherry is really about! As I said before, sherry winemaking represents a very unusual approach, philosophy and history within the winemaking world and I learned quite a bit about it during my trip to Andalusia. That’s why I would like to share some of this sherry knowledge with you along with my take on it.

Sherry is made from two grape varieties – Palomino Fino and Pedro Ximenez. The first one is used to make dry wines, the second is used for dessert wines. All types of sherry from the Jerez region are fortified wines. It means that once the regular grape fermentation is done, the wine is supplemented with a distilled 40% grape spirit. Depending on the sherry kind, the final alcohol content is between 15-20%, while the sugar levels vary from tiny to mind-blowing 450g/l.

It was clear from my tour guides that the major part of the sherry making process takes place in the bodegas themselves. The grapes, fresh or already fermented, as well as the grape spirit are ordered by the bodegas from an external producer(s). Sherry makers practise their craft in the bodega, where common wine disappears and sherry comes to life. The art of making sherry lies in mixing of the vintages, ageing and resting the wine under very specific conditions. The origin and quality of the produce seems to be of secondary consideration. It’s not that it doesn’t matter, it’s just not really a part of the “official” sherry image and brand. This approach to winemaking is in stark contrast to the broader trends in the industry, where the importance of soil, climate, farming practices, etc. become more and more prominent. Many winemakers pride themselves in their minimal interference in the winery after the grapes are picked. They aim for the terroir (the complete natural environment in which a particular wine is produced) to speak through the grape. For example, this philosophy is ardently followed in Alsace (more details to follow in my next post).

A special method, the solera system, is used to produce sherry wine. Simply put, the solera refers to stacked up rows of wine barrels, usually three. The top row carries the youngest wine, while the bottom one the oldest. Every year, in order to bottle new sherry, some of the liquid from the bottom barrel is removed, but never more than 30%. To fill the gap in the ground barrel, some of the wine from the middle row is transferred down. Similarly, the top row refills the middle row while brand new wine is added to the uppermost level. As a result, the final sherry in the bottle is always a blend of different vintages. This is exactly what a sherry maker aims for – consistent and predictable taste. Vintage fluctuations caused by changing weather conditions and the multitude of other factors are smoothed out by constant mixing.

Most bodegas make all sherry varieties. Fino, amontillado, oloroso and palo cortado are the dry sherries. Palo cortado is an elusive type of sherry with a really mysterious origin story. It’s a bit far-fetched for my taste, so I won’t go there for now. There is also manzanilla, a type of fino, that can only be produced in the third town of the triangle – Sanlúcar de Barrameda. The dessert sherries are cream and Pedro Ximenez (PX). Recently, some local producers also started to make vermouth.

Fino is the youngest and freshest of the sherries. During the fermentation in the barrel, wild yeast forms a thick layer at the top called flor (flor, Spanish for flower). The yeast blooms like a flower. The flor blocks the oxygen from making contact with the wine. Hence fino doesn’t get oxidised and remains very pale, almost colourless. Wine makers leave the barrels only three quarters full to facilitate flor formation. Tasting in Lustau featured three different finos, each produced in a different town of the sherry triangle. Nevertheless, I enjoyed fino from Gutierrez-Colosía the most. It was the most elegant and understated, with prevailing citrus notes and sharp saltiness – very fresh, yet unique combination. Chamomile notes were also very pronounced. Now, a disclaimer: my very first encounter with fino was a shocking experience. I hadn’t tried anything like that before. It took me some time to get used to this style of wine and to actually be able to appreciate it.

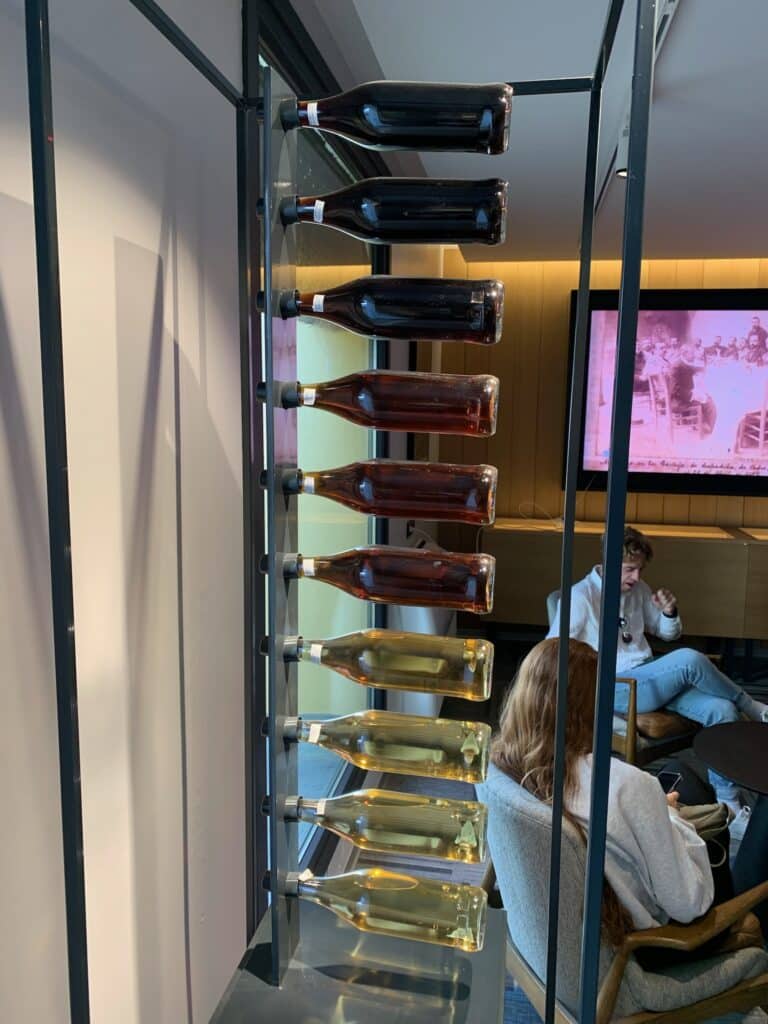

Amontillado and oloroso are aged for much longer and in a different manner. For these styles, oxidation is crucial. Amontillado starts the same as fino, however at some point the flor is removed to let the oxygen in. Oloroso does not age under the yeast layer at all. Due to the oxidation and longer time in the barrel, these wines are much darker than fino. Dry wines from Gutierrez-Colosía reach the market when the youngest wine in the blend is at least 8 years old. I even tried a Lustau sherry in which the youngest “part” was 30 years old! This type of wine even receives its own regulation VORS which stands for very old rare sherry.

Sadly, amontillado and oloroso from Gutierrez-Colosía were not for me. They were quite acidic and lacked balance. The taste of pure alcohol was very strong as well. On the other hand, amontillado and oloroso Emperatriz Eugenia from Lustau are worth mentioning. Amontillado had a sweet aroma of caramel and nuts, but it was bone dry without a trace of sugar. Rather acidic and salty, it tasted of spices and mushrooms. Certainly, an acquired taste, but I was quite prepared this time after having tried a few finos. Oloroso Emperatriz Eugenia is 20 years old. Similarly sweet on the nose, there were clear orange, caramel and wet wood notes. Taste-wise, apart from lime and orange I also got a hint of dark chocolate. The wine was powerful, yet balanced nicely with a long finish. Beware, 20% alcohol content might pose a challenge for less seasoned drinkers.

Cream sherry is quite a sweet wine, but not always considered a dessert one. Cream from Gutierrez-Colosía is a 70%-30% mix of oloroso and PX. It gives notes of wet wood and tastes of raisins and dried fruit. Overall, this wine only hints on sweetness and is predominantly dry. I found it very intriguing.

There is no other dessert wine like Pedro Ximenez. Sugar content can spike up to 450 g/l, so even a small glass can give you a kick thanks to its overwhelming honey-like sweetness. Dried fruit, caramel and chocolate dominate. For my cellar at home, I selected a PX from Lustau, which wasn’t included in the tasting. But their wines showed good structure and quality across the range.

Last but not least, I would like to highlight red vermouth from Lustau. When tried for the first time, Martini and other such drinks come to mind. However, Lustau’s vermouth is far ahead of the mainstream mass producers in terms of its flavour balance and precision. It was a pleasure to enjoy a combination of extremely refreshing orange and spices that reminded me of Christmas and ginger cake. Truly, 10 out of 10 in the aperitif department. It was a perfect way to get ready for dinner. Especially in Spain, where dinner is often not served until 9pm which is a bit of a challenge for me. A glass (or two 😉) of vermouth with just a slice of orange and a large cube of ice was a mandatory start to a tapas-filled evening.

Discovering the world of sherry was a big adventure for me. Perhaps my greatest wine adventure so far. Maybe even too exciting and unexpected to unWined. I tried everything: from teeth-gritting finos to molasses-like, super sweet Pedro Ximenez. The range of sherry wines is absolutely amazing and unique. Vermouth too, took me by surprise! An amazing experience for sure, but I decided not to bring too many dry sherries home. A bottle of fino, more as a souvenir, not to quietly enjoy and reminisce about my time in Spain. I really get it now how niche the sherry world is, what it offers, why more and more bodegas are shutting down and/or limiting their production. Most sherries are simply a challenge for an average wine drinker, who’s not accustomed to its unique flavour profile. Sherry is doing fine locally, thanks to the strong tradition and because it goes well with local cuisine. Fino is particularly great for the abundant local seafood dishes. Outside of Andalusia, it might lose some of its charms. Even more so for casual drinking. As always, I recommend the sherry triangle to everyone, but the more adventurous wine lovers in particular. Those feeling less brave: please, consider yourself warned!

Bodega Lustau: https://lustau.es/en/.

Bodega Gutierrez-Colosía: https://www.gutierrezcolosia.com/Inicio/.

Więcej nieWinnych Podróży wprost na Twoją skrzynkę? Zapisz się!